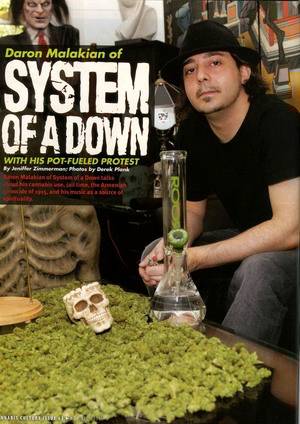

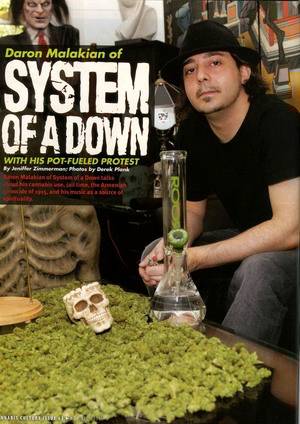

Daron Malakian of System of a Down talks about his cannabis use, jail time, the Armenian Genocide of 1915, and his music as a source of spirituality.

System of a Down won the 2006 Grammy for Best Hard Rock Performance, was the first band in history to debut two different studio CDs (Mezmerize and Hypnotize) in the #1 spot of the Billboard 200 during the same year (2005), and was nominated for an American Music Award as “Favorite Artist” in Alternative category. They sold in excess of 800,000 copies of their fourth studio release (Mezmerize) and subsequently reached platinum status, earning a place at #1 on the charts in thirteen different countries.

But these recognitions are neither System of a Down’s motivation, nor the reward they seek. System has brought awareness to social injustice and international issues, including the Armenian Genocide of 1915, an atrocity that continues to be denied by the Turkish government. As Armenian-Americans, the subject is deeply personal for all four band members: Vocalist Serj Tankian, guitarist Daron Malakian, bassist Shavo Odadjian, and drummer John Dolmayan. Benefit concerts, such as the annual Souls show each April, support organizations like the Armenian National Committee of America (ANCA) that publicize the horrors of genocide and atrocities against cultures.

System of a Down’s music is intense, potent, complex, and defies classification. It sounds like middle-eastern-tinged heavy rock fuelled by protest and rebellion. “A lot of people like to focus on the heavy side of System of a Down,” Daron Malakian told Cannabis Culture, “but I think it’s a fusion of so many different styles. I listen to, and take in, a lot of music and it all kind of shoots out of me like a blender.”

System of a Down’s music has had a political effect on fans. The widely acclaimed song “Boom!” (Steal This Album) was accompanied by a video directed by Michael Moore, and fearlessly released during a time in the United States when those who spoke out against the administration were considered anti-American. The video gives witness to thousands of protesters worldwide demanding peace through System’s lyrics: “Every time you drop the bomb, You kill the god your child has born, BOOM! BOOM! BOOM! BOOM!”

For many enthusiasts, the band’s name has become synonymous with global action. However, Malakian resists the message that they are part of any political agenda. He considers himself more an individualist than an activist, and is not provoked or impressed by awards or fame—for example, his Grammy still sits unopened in a box in storage.

He was born in California on July 18, 1975, to a family of artists who relocated from Iraq to Hollywood, and is a self-taught musician who learned to play by ear. He’s also a self-proclaimed “wake-n-baker” who was “stoned, and then some” during the creation every CD.

Cannabis Culture: I understand that both of your parents are artists.

Daron Malakian: That’s something that inspires me a lot in my life. My dad never made too much money doing paintings, but he’s always done his paintings. It hasn’t been about the money; it’s been about passion, [and] that’s the one lesson I try to stick with. Even thought I’ve made money with my art, I try not to focus on it. I try to focus on the art.

And that is something that comes from my dad, watching him paint really brilliant pieces of work throughout my life, and nobody got to see them except my mom and me. But he kept doing it, and he didn’t even care to show people. It was just [for] the fact that he loved to do it.

And that’s really how I feel about music. If people want to hear it, that’s great, and I’m very lucky that people do. But, if they don’t, I’ll still do music, even if I’m the only guy who hears it. It’s just a way for me to express [myself]. If I didn’t have that, I’d…you know…I wouldn’t see a reason to even exist if I don’t have that.

CC: A lot of that passion is lost in the music industry today. Many people aren’t following their passions, or even asking themselves what their passions are.

DM: Everything is put into a cubicle and sold and marketed a certain way, and we’ve become a number and a statistic to people who sell Coca-Cola and hamburgers and clothes, or whatever the hell they sell, and music has become one of those things that has fallen into those categories.

System of a Down was playing clubs in the late 90’s, and we were playing packed houses, and labels didn’t want to sign us. I had people come up to me and say, well, the black people won’t understand you, and we can’t sell you to the white people because you’re Armenian. I’ve actually had that said to my face! And that just showed me where it’s all at. So we’ve just done it the opposite way.

The way I’ve approached my song writing has been completely, like, I don’t sit there and listen to the radio, and say, hey let’s see what’s playing on the radio so I can play a song that matches up to that. You know, you shit what you eat. When someone is crying, someone is crying. You can’t market that.

And that’s what art is, someone showing his or her emotions. So all I’ve done with my song writing is be honest: cry for real, laugh for real, get angry for real, say things that are honest in the song—and people are listening because everything else they are getting isn’t as honest.

CC: The word that comes to mind is regurgitated.

DM: In the 60’s, songwriters and musicians were respected as artists. Music has now become separate from art. Music is music and art is art. For god’s sakes, they’ll call Paris Hilton an artist if she puts out a record. So you know, that’s where you are. What happened to the John Lennons, the David Bowies, the musicians that were innovating because they were being motivated to innovate? People respected what they did because they weren’t clumped in with Pepsi. Yet.

CC: It had been said that people aren’t looking to the politicians for answers anymore; they are looking to musicians. What do you think about that?

DM: I’m not sure the people are looking to anything. There is a war going on, we have troops in Iraq, we have troops in Afghanistan, we have troops going to Lebanon, there is havoc all over the world. My television isn’t on often, but for days they talked about the JonBenet murder from ten years ago. It’s a distraction from the vital problems we have right now and some people don’t see that.

System of a Down just played the Ozzfest for 20,000 people, and when Disturbed was on stage right before us the whole crowd was shouting “USA! USA!” almost like a Nazi chant—no offense to Disturbed—and we would sit there every night and say ‘I can’t believe these are our fans! They like us too!’ I have nothing against the US, but you say Seig Heil, USA, or whatever the hell you say with that kind of propaganda-motivated type of chant—it’s just scary to me.

Then we get on stage, and we say our thing, and they cheer for that too. That’s why when you say they listen to the musicians, or they listen to art, I’m not sure. I think it’s like sheep, and it’s wherever they are herded to. I’m not saying that’s everyone, I’m just saying it’s a big part of this nation.

CC: How much has your perspective been influenced by your family being from Iraq?

DM: Well, actually, I went to Iraq in 1989 when I was 14 years old, and spent two months mainly in Baghdad. Up until then, even though my family was from another country, I was a typical American kid. I remember…as a kid I had no beef with President Reagan, with anybody.

When I went to Iraq I thought it was going to be dirt roads and weird dirty people and terrorists, and I saw quite the opposite: very nice, gracious people, and very scared people because they were living under Saddam Hussein and had been involved in a war with Iran for eight years at that point.

If Americans really saw how the Middle East was, they wouldn’t pass judgment the way that even I had before that point in my life. When people are scared they usually aren’t arrogant, they’re kind. And I’m not saying we should go scare people into being nice—those are just the circumstances.

CC: It helps us realize, it doesn’t matter if you are in a position of power, if you’re rich, famous, or if you’re just the guy on the street; what we all have in common is that any one of us can die at any time, and knowing that brings a sense of humility and appreciation for life.

DM: That is so personal to everybody. You can die with thousands of people at the same time, but you’re still dying alone. So, I come back from Iraq—and at this point it’s 1990—and I saw the kind of propaganda that was going on in the US news and press, and how they were portraying Iraq and the Iraqi people, almost making Saddam Hussein and the Iraqi people one and the same.

Now, if I had never gone to Iraq I would have thought: Wow, they are all one people. But after going to Iraq, I realized that this was all propaganda. And for the first time in my life I realized what propaganda was, when I was 14 years old. And that changed me.

Yes, my family lives in Iraq, but it still took my own experiences to realize that there are things going on that most of the general public has blinders to. It’s not their fault; they just haven’t seen it.

CC: How did your folks decide to move to the US?

DM: Around 1975 they started to see changes in the government. And it wasn’t just my folks; it was almost half my family. I have a huge family, and half came to America and the other half stayed in Iraq, and they are still there. I mean, my dad is an artist and I don’t think he wanted to live in a society that said you couldn’t make that kind of art.

[My parents] are really open-minded. They saw the changes that were happening in the country so made their way over [to the US]. At that point, a lot of people in the Middle East never had any problems with the United States. My mother used to say that when she was young she looked up to the United States and she loved the culture, just like a lot of people in the world.

In Asia, the Middle East, Europe, people used to look to the US as a heroic nation of people. Many of the third world’s favorite actors and musicians come from the United States, or music-wise they come from England and the US. The western culture was never something that was so anti-Middle Eastern. My mother grew up singing and listening to the songs of Nat King Cole—you know what I mean? Now tens of millions of people in those places have changed their opinions of the West, because of the politics [foreign policies] of the US.

CC: Are you aware of the American intention to extradite Canadian Marc Emery to the US because of his political activities and the mail-order seed business that facilitated his political activism? If that happens, Canadians will be enraged. That’s what the 60 Minutes (television) segment about Marc conveyed to me.

DM: Let’s not kid ourselves: America is pretty much the empire of the world. Now, if Canada came over and did that in America, the US feds would be having none of that. It’s absurd because in California we have the pharmacies, and it’s [also] a place where you get a medical marijuana card and buy weed, and nobody screws with you. There are hundreds of these marijuana pharmacies in California. It’s kind of amazing to me, and the first time I saw it I thought: This can’t last; this won’t last! But it has endured for over ten years now despite the Drug Enforcement Administration’s determination to shut them down.

I guess it just makes me think that things might be changing for the better. This is a big indicator that society—at least in California and the western states—are broadening their outlook on pot. If you want to talk legalization, what we have now in California is a very big first step.

CC: Do you feel like smoking herb helps you, as a musician, with your inspiration?

DM: Oh , I wake up and smoke, man; I’m a wake-n-baker. I smoke an insane amount of weed…nobody should smoke that much. I was in Amsterdam and I was invited to this shop where there were seventeen or eighteen different types of weed listed by name, and the guy told us we could smoke as much as we want. I was like, ‘this is fucking great!’

So I sat there and graded them, and I don’t know anything about the biology or growing of weed but I wound up picking the best shit. He said one in five hundred smokers are able to smoke as much as you; and he said nobody ever picked the top five before, and I did. And I said I don’t know anything about it, except the ones I like.

CC: Do you remember which ones you picked?

DM: My favorite one was called Neville’s Haze.

CC: So how much does smoking weed play a part in your creativity?

DM: For me, I’m a very ‘up’ person, and it takes a little bit of the edge off. I mean, every record I’ve written I’ve been completely stoned, and then some. But I can’t say I couldn’t write without it. It’s also nice to listen to music when I’m stoned. That’s one of the joys of getting stoned, listening to music.

People might say that pot is a gateway drug, but I think that depends on the person. I know plenty of people who smoke only pot and I’m unaware of any other vice they might ingest. In my lifetime, I’ve seen a lot, lot, lot more destruction and negativity from alcohol, and I don’t drink. I used to, but I haven’t since I was 21 years old, over ten years ago. I’ve seen a lot of really bad things in my life from alcohol.

And then there’s tobacco and shelves and shelves of toxic products in our supermarkets and malls that are proven to kill, and all of them legal. But cannabis isn’t. We are trained and programmed to not even go with our hearts anymore. The state gives us permission to wake up in the morning and drink caffeine and smoke a cigarette, but don’t smoke pot.

I’m not saying your children should smoke weed, but I am saying that your children are probably better off smoking weed—certainly safer—than downing a twelve-pack of Budweiser everyday.

CC: Many, probably most of Cannabis Culture’s readers are unaware of the Armenian Genocide. Can you talk about that and why that terrible incident in history is important to you?

DM: Some people look at it as a political thing. For me, it’s a personal thing. The Turkish government is putting out some bad propaganda about System of a Down, and it’s gotten to the point where our label in Turkey doesn’t even want to represent us anymore. But, it’s all lies. They said things like we wrote on our ticket stubs “No dogs and no Turks” which, of course, is outrageous; we’ve never done anything negative like that. The Turkish press deliberately misleads the public there about our message.

We’ve never said we have a problem with Turkish people. We don’t have a problem with Turkish people, to be honest with you. It’s just when you have great grandmothers, and my grandmother, and all Armenian grandparents still alive who went through this genocide (in the eastern part of Turkey from 1914-1915) and the Turkish people hear from their government that it didn’t happen, you are going to have some resentment.

However, if the schools aren’t going to teach people the truth, we feel that it is our place as Armenians to do so since we are in a place where people are going to listen to us. As an Armenian, you are obligated to say something about it when you are in a position of being heard.

(Editor’s Note: One and a half million people were exterminated to suppress Armenian independence. Turks refuse to face up to this atrocity and hideous time in their history. The government of Turkey denies it ever happened. Even though genocides take place on a fantastic scale requiring tens of thousands of executioners—in Cambodia, Rwanda, and Armenia, as examples—it’s maddeningly difficult afterward to ever find any person or government or official who admits to being responsible. As such, victimized people feel a scalding resentment because there is no official acknowledgement of their incredible suffering and annihilation.)

CC: Why do you think Turkey refuses to account for its actions?

DM: It’s a political issue. Turkey doesn’t want this to be recognized, because they feel they’ll have to make restitution in land and money. What’s going on with Turkey would be the same as Germany saying the Holocaust didn’t happen. The Armenian genocide was planned out the same way the Nazi ‘Final Solution’ was planned out. When you look back at Hitler’s memoirs, there is a statement that he made that said, “Who remembers the Armenians?”

(Editor’s Note: a speech by Adolf Hitler to Wehrmacht commanders at his Obersalzberg home on August 22, 1939, a week before the German invasion of Poland, included, “Go ahead…kill without mercy. After all, who now remembers the Armenians?”)

So he thought he could get away with the Holocaust because the Turks got away with genocide. I think, out of everyone in the band, I write songs and leave it there. I don’t get politically involved or talk about it. I’m aware of a lot of politics, but I don’t necessarily want to be seen as that [kind of] guy. Serj gets involved in it politically [but] I try to focus on the art, the music, and my spirituality.

CC: You were asked to play at the Grammy Awards this year. What was the conversation you had as a band when you received that invitation?

DM: We didn’t even have a conversation—we just didn’t do it. We won the Grammy, but we didn’t go to accept it. It’s not about trying to be cool rock stars. Do you see all the other people who win? They suck. I mean…it was cool for my mom.

The Grammy was sent to me in a box, and I still haven’t opened it yet. Hey, I won, but does it really make or break my day? Not really. I still lose sleep over the next song I want to write. That’s where all of my energy goes.

CC: What was the inspiration behind ‘Prison Song’?

DM: It touches upon so many different things. Serj and I both wrote lyrics on that song. I came up with the theme of the song, “They’re trying to build a prison.” The song was inspired when I actually went to jail, and I wrote it when I came home.

CC: What did you go to jail for?

DM: I had some warrants…Anyway, I came home and wrote the theme about prison, and Serj brought in the whole prison system and the way it works, the statistics. And to me, you can look at it like the prison systems are so over-populated not with murderers and pedophiles and violent criminals; mainly people who get caught with drugs.

You stand back and look at that, and say, is this making my society safe? I mean, they way the system is working, isn’t working.

CC: Michael Moore was involved in your video for ‘Boom!’ How did that come about?

DM: Well, that was a really emotional time for me. It was before America actually went into Iraq and I was really scared, clinging onto hopes that they wouldn’t go, because half my family lives there. That was from Steal This Album (2002) and we promised ourselves that we wouldn’t tour or release singles. We just wanted to put the record out.

We had a song called ‘Boom!’ and we thought hey, we could say something with this song. We had heard director Michael Moore (Bowling for Columbine, Fahrenheit 911) was a fan, and we thought it would be interesting to collaborate and make a video with the song. We just felt like we had to say something at the time.

I don’t have a high school diploma, but I predicted this problem in Iraq…so we were really just saying please, war isn’t right. Maybe we can make young kids see this video, and maybe young kids would get up and protest and do something. We thought Michael Moore was one guy who had balls.

In early 2003, everybody was hush-hush, nobody wanted to talk against the war—it was almost treason. If you talked against the war you were ostracized. So we were like, who has the balls to say something with us?

CC: Michael Moore was at the height of controversy at that time.

DM: To be honest, we never actually met him. He sent his whole film crew, and I spoke to him on the phone briefly, but I never met him. I like what he does and I think he’s cool, but I’m not a dogmatic leftwing guy. I like to understand the right too. I’m perhaps the guy in the middle. I’ve got to try to understand the other viewpoint, so I can have an opinion that’s more thought-out. Thing is, I’m not and America-hater.

CC: I love the song ‘Holy Mountains.’ What is that song about?

DM: The song is about Masis (the Armenian homeland) and Ararat (a mountain in eastern Turkey considered to be the landing point of Noah’s Ark). If you saw the mountains on TV they would be described as mountains in Turkey, and that’s always a knife in an Armenian’s heart because those are Armenian mountains, not Turkish mountains. They were stolen from us.

So that song, ‘Holy Mountains,’ is about those mountains and how they were stolen from us. [Also], my little cousin’s name is Masis.

CC: How much does your spirituality play a part in your music?

DM: My spirituality is my music. I have no power over writing songs. What I do is pray a lot so I can get closer to God, and in my case, praying is focusing and listening to music. Not just music, but all kinds of art, and that is the way I get closer to my higher power.

By Jeniffer Zimmerman; Photos by Derek Plank. Article from "Cannabis Culture" Magazine (Nov/Dec 2006)

Êîììåíòàðèåâ: 1

_____

Âàðíèíã! Òóò ñåðâåðó ïåðèîäè÷åñêè ïëîõååò è MySQL îòâàëèâàåòñÿ ñ îøèáêîé, à ÿ ïîêà åùå íå íàøåë â ÷åì ïðè÷èíà, ò.ê. ñàì â ýòîì íå î÷åíü õîðîøî ðàçáèðàþñü. Åñëè ó êîãî-òî åñòü æåëàíèå ïîìî÷ü ïèøèòå ìíå, ëó÷øå íà ïî÷òó.

Òîæå â ìóøêåòåðû ðåøèë çàïèñàòüñÿ?